The ending or endlessness of artworks

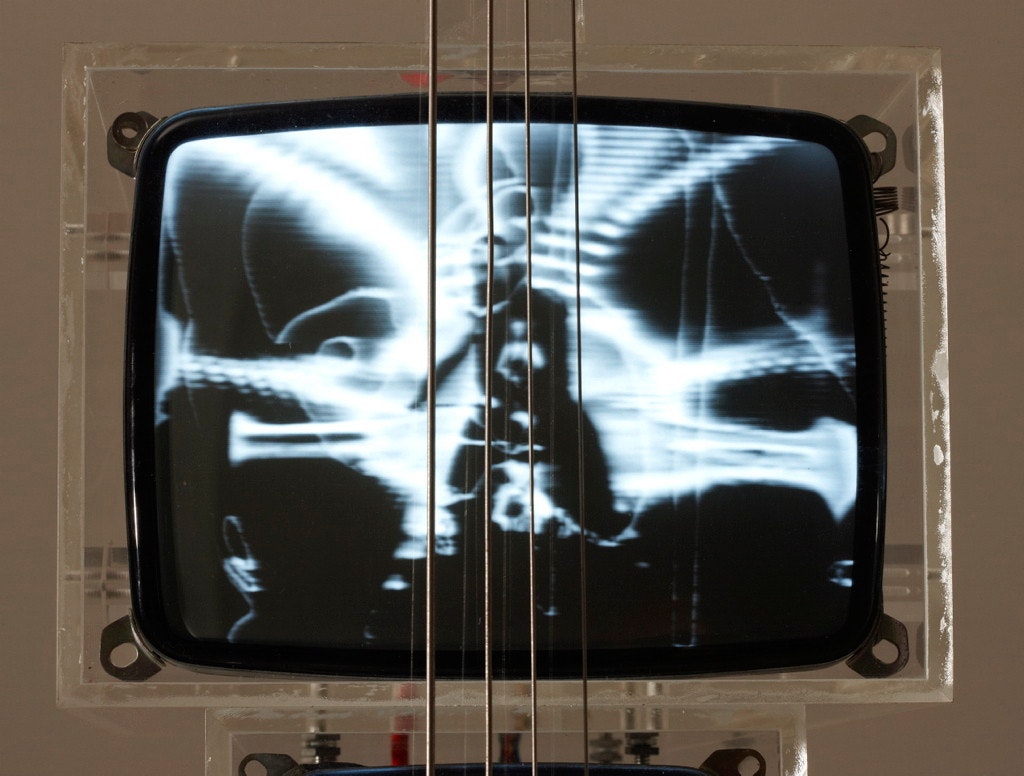

Nam June Paik TV cello 1976 (detail). Art Gallery of New South Wales © Nam June Paik Estate

We’re not computers, Sebastian. We’re physical.

Is art alive? Sometimes it feels like it is. After all, an artwork can speak, guide and challenge a museum from the moment it enters a collection. But what if an artwork is missing pieces or it no longer functions as originally intended? Would it still be the artwork? Would it still be alive?

Museums were invented to collect and preserve against the tides of change, but as materiality morphs into ephemerality, the art museum is increasingly acquiring variable, immersive, virtual and participatory artworks into our collection. And so we must ask ourselves, do museums need to change in order to collect, display and preserve the art of the now?

Asti Sherring, the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ senior time-based art conservator, and conservation technician Jonathan Dennis join Louise Lawson, conservation manager of time-based media at Tate, UK, and Kate Lewis, Agnes Gund chief conservator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for a discussion on the future possibilities of art collections, the mortality of an artwork, and what it means for art conservators to preserve artworks that are no longer made to last.

Jonathan: This year has shown us how quickly and irrevocably things can change. It has highlighted the growing requirement for a museum to be flexible and adaptable. How have your art museums responded to this changing art world?

Louise: In this changing global landscape, and with new COVID-19 restrictions, we are focusing on our collections. This is a real opportunity for collection care divisions, who engage directly with artworks to enthusiastically support different ways of accessing our collections. I won’t lie, the last day Tate was open to the public, Tuesday 18 March, I realised the gravity of what was happening as we switched each artwork off. This was hard as we had spent so much time preparing these artworks for the public. And that usual joy of seeing an exhibition open to the public was cut short. It was really quiet.

Kate: MoMA shut down on 13 March and we’ve only just reopened, with restrictions in place. It’s been amazing to see how adaptable people are, how new ideas and creativity have prevailed during this period. Our staff are thinking in new ways; in part because we always have to, but now we are on an accelerated timescale. For example, art museums have been looking to further develop their presence in the virtual realm for some time, now we have no choice.

Asti: One of the most important roles of the art museum is to create connections and community through culture that expands beyond a gallery’s physical walls. In many ways, this moment has allowed us to be fearless with our audiences. We’ve been able to tell unique and diverse stories through our collections, experiment with new platforms and modes of communication – all of which allows us to deeply reflect on what a 21st-century museum can be.

Jonathan: In this sense, how do you see contemporary artists challenging museum collecting practices?

Louise: One example from the Tate’s collection that has pushed us to think about what we do and how we do it is Tony Conrad’s 10 years alive on the infinite plane 1972. This is a complex performance and multimedia work that includes the live performance of a musical ensemble and the 16mm projectionist. It is the first performance work by the artist that we’ve collected posthumously, which made us realise the magnitude of what it means to collect a performance work when the artist is not there.

Jonathan: Without the artist, how did Tate go about establishing and capturing the identity of the work?

Louise: In 2017, Conrad’s collaborators came in to discuss the significant properties of the work and how we might activate and document it at Tate Modern in the future. The artwork’s complexity lies in the fact that the performance does not follow a specific score, and, historically, it relied on the performers and their previous experience of playing the piece. This artwork then became a key case study as a part of Tate’s research project Reshaping the collectable: when artworks live in the museums in 2018. This project facilitated a deep understanding of the complexities such an artwork presented.

Asti: What does this process mean, to restage 10 years alive on the infinite plane?

Louise: As part of the work’s activation in 2019 at Tate Liverpool, we created documentation that was provided to a new set of performers who didn’t know Conrad’s work. We relied on a network of experimental music musicians and a 16mm projectionist, who performed the work based on the documentation created by Tate. Conrad’s previous collaborators were invited to the performance to critique the process, which allowed us to reflect on the work and adjust the documentation. It was a very fulfilling exercise.

This process made us realise that the biggest thing missing was, of course, Tony Conrad. We felt we needed to do more in our documentation to capture his personality, the characteristics – positive and negative – that made him who he was as a person.

Asti: Artists have always used the mediums of their time. Can you think of an artist who’s pushing the boundaries of the mediums of today?

Kate: One work that comes to mind is Josh Kline’s Skittles 2014, which was acquired by MoMA in 2015. The work is a huge glass-fronted commercial refrigerator, like you might see in a grocery store. The refrigerator is backlit, and behind the large glass doors are 15 different flavours of juice, lined up on the shelves. The work is inviting you to open the door and pick one of these juices, but each flavour has a surprising list of ingredients. There’s a flavour called ‘Big data’ which contains fragments of Google Glass eyewear, shredded Verizon phone bills, Omega-3 fish oil, porn and Purell (Purell are one of the main sellers of hand sanitiser in America, taking on an enhanced meaning at this time). There’s another one called ‘Supplements’ which includes the ingredients Rogaine, blueberries and Viagra.

Jonathan: How did MoMA prepare the artwork for display in the exhibition New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century in 2019?

Kate: MoMA’s conservation lab became a juice-making lab. We acquired all these materials and then made juice. For five days, conservation, curatorial, fellows and interns made a juice production line. And as we were juicing and smashing Google Glasses, we were thinking, ‘what will this mean over time?’ As well as this, practical questions came up, like how do you add a bit of tennis ball? How do you blend a tennis ball?

Asti: That’s one hell of a team-building exercise!

Kate: As you know, we conservators are very precise, meticulous people. The team got very good at making the juices, and in addition to the information that the artist provided, they also compiled a cookbook.

Asti: Does this production line need to occur every time the work goes on display?

Kate: Yeah. At the end all the juice has got to go. Even during display the juice aged, changed colour, frothed and grew mould.

Jonathan: What will this artwork look like in the future?

Kate: This artwork references a specific moment, Josh Kline said that he was ‘thinking about downtown New York’s class problems in the wake of the financial crisis’. The artist was capturing a moment in American culture and MoMA wants to be able to keep showing the artwork. We have stockpiled some materials like Google Glasses and tennis balls, but there were certain things that we wouldn’t want to store alongside paintings and sculptures, such as Coca-Cola. So we’ve had to make decisions about what to store and what to source each time the work is scheduled for display. But even within three years, some of the materials have become more difficult to obtain.

Asti: When I think about the future of the museum, I often end up thinking of an art collection store and a place where artworks go to rest. However, with contemporary art, there is more risk of the collection store becoming a graveyard for broken, deteriorated things.

Louise: So maybe it’s not always the physical stuff that will always remain? For example, Naum Gabo’s modernist sculptures used new materials of the time, such as plastics. But many plastics are unstable, which means that Gabo’s works have deteriorated, turned brittle, cracked and no longer represent what the artist originally constructed. In these instances, we’re basically nursing these objects into the afterlife.

Martin Creed Work no. 2821 2017, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Martin Creed/DACS. Licensed by Copyright Agency

Asti: The lack of physicality in some contemporary artworks can be considered a positive attribute. One of the opportunities of conceptual and variable artworks is that they only exist when they go on display. Take, for example, Martin Creed’s Work no 2821 (half the air in the given space) 2017, in which yellow balloons fill a percentage of a room based on the volume of air in the space. For the Gallery to achieve this installation, we were given an equation by the artist that would allow us to accurately determine the number of balloons required. The artist also provided us with a set of guidelines and specifications on the colour and type of balloons that need to be sourced each time the work goes on display. The work is participatory in that the audience is invited into the space. I gotta tell ya, when you’re immersed in a balloon room, it’s hard to wipe the smile from your face.

Louise: This resonates a lot with performance works, because as quickly as they appear, they disappear.

Jonathan: The Gallery has recently done a deep dive into the legacy of Nam June Paik and collaborator Charlotte Moorman’s TV cello, a seminal performance that happened at the Gallery in 1976. It has become clear through our research that our TV cello was one of only four video sculptures that formed part of a performance, rather than being a standalone work.

Asti: What this research has revealed is that the work is more than its functioning components. It is in fact part of a performance and belongs within a rich archive of important events in media art history.

Jonathan: Unfortunately, the video sculpture stopped functioning while on display in the 2019 exhibition Making Art Public: 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects, but our research helped us determine a conservation strategy that ensures we are safeguarding all the components of the work as well as preserving its performative history. While the relevance of the artwork’s material past is a significant component in the work, in this case, our decision-making was based on the conceptual nature of the performances and the artists’ intentions. As time travel is not option, this preservation strategy brings us as close as possible to an authentic experience of the work.

Nam June Paik TV cello 1976, installation view from Making Art Public: 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Nam June Paik Estate

Asti: Is there ever a point at which an artwork has reached its end of life? Is there always an afterlife for art?

Kate: Let’s step back and think about art that really is old. Like the Winged Victory of Samothrace, a 2nd century BCE marble sculpture, held in the Louvre’s collection in Paris.

When you see the work on display now it is an iconic winged female figure with no arms and no head. But at some point in time, before it was acquired into the Louvre’s collection, it would have been a complete figure with limbs, a head and perhaps even a facial expression. There’s a lot of debate about why and when it was made, and different scholars have different theories. There is also evidence that at some point in time one of figure’s wings was completely remade. This sculpture is a mystery on many levels. So, even though it is incomplete and partially restored, I would re-pose your question: has this sculpture reached the end of its life?

Asti: Or is the question of what’s remaining irrelevant, because it is an object in the Louvre’s collection, which continues to be displayed?

Kate: Now that this work is in the Louvre collection, it has a different kind of history and relevance to society. Interestingly, this work was recently featured in Beyoncé’s ‘Apeshit’ music video, so clearly it’s still relevant. Even though there’s a lot of stuff that has happened to the sculpture that we don’t know about, there’s something that is still of interest to the public who visit the Louvre and there is something about the artwork that resonates with contemporary culture.

Winged Victory of Samothrace c190 BCE. Photo: Gary Lee Todd, PhD, used under Creative Commons License 1.0

Winged Victory of Samothrace c190 BCE. Photo: Gary Lee Todd, PhD, used under Creative Commons License 1.0

Jonathan: Can we still aspire to keep art forever?

Louise: When considering the act of collecting – of acquiring artworks into public collections, to preserve and display forever – the ongoing question of how artworks may change and evolve over time is something that everyone is grappling with. It is just more polarised in contemporary art, as many of the materials that artists use today are not made to last. In many instances, conservators cannot reverse decay or obsolescence. Instead, conservators are tasked with managing the inevitable change in artworks that we care for.

Asti: That’s why taking a reflective approach to the care of our collections is so important. There has always been the perception of objectivity in the museum, the idea of adhering to objective truths. Contemporary art helps us to rethink these traditional notions and our custodial roles to not just manage the changes that may occur in an artwork, but to also engage and reflect on our role in the life cycle of an artwork.

Kate: One of our roles as custodians is to gather information about the artwork that relates to this moment in time. With contemporary works we are able to interview the artists to create primary sources, and document how and why artworks are displayed in certain ways. These acts, we hope, will contribute to a greater body of knowledge, so that in the future others can reassess, and each generation will have these contemporary sources from which I think they will make their own decisions about what is best for the work.

Louise: Fifty years from now, it’ll be interesting to know how people reflect on the work that we are currently doing, and how we approached and thought about these big questions.